The Case for the Collaborator: Native Voices in the Italian Empire

- Andreus Et Bonumagra

- May 19, 2025

- 4 min read

In discussions of colonialism, Italy is often cited as an example of a particularly egregious imperial power—violent, racist, totalitarian. Yet, missing from these narratives is a broader exploration of what those governed by the Italians actually thought. While we must not minimize the acts of violence, exploitation, and devastation that occurred under colonial regimes, an exclusive focus on abuse oversimplifies complex historical relationships.

Modern academic narratives tend to frame colonized peoples in very narrow roles: either as victims, rebels, or revolutionaries. This is an ideological lens, often influenced by postmodern or Marxist thought, in which indigenous agency is only recognized when it serves an anti-colonial or anti-Western narrative. Rarely are colonized people allowed to be seen as collaborators, loyalists, or even just everyday individuals participating in society. This is problematic not only from a historical perspective, but also because it can be subtly racist. It assumes that colonized peoples lacked the independent will to make decisions outside of reacting to white oppression. In other words, they only exist in relation to the misery that is paid them. Yet, there are others that counter this narritve.

To illustrate this, consider the Kunama people of Italian East Africa--- Eritrea. Italian colonialism in East Africa began like many imperial projects: commercial ventures set up outposts, which were followed by governmental structures and bureaucratic control. As with any new arrival in human history—whether in schools, families, or businesses—conflict ensued as people adjusted to new hierarchies. Thus it shouldnt be strange to us that some resisted the Italians; others saw in them an opportunity.

The Kunama are an example of the latter. Historically marginalized and vulnerable to raids from other groups—particularly the Abyssinians—the Kunama experienced a rare period of peace and stability under Italian rule. Do not take this author's word for it. In interviews recorded in the study Memories of the Kunama of Eritrea Towards Italian Colonialism, we find illuminating primary-source reflections. One male informant recalled:

“During the Italian period there was peace in our region. We were able to travel to the areas of former enemy groups without any fear. Everything was cheap and available... The Italians ordered us to build roads. They gave to us flour and clothes for the labor we performed.”

A female informant remembered:

“The Italians used to invite us on festive occasions where we sang and danced... For the dances we performed during such celebrations, the Italians slaughtered cattle for us. They also gave to us clothes, mirrors and other things.”

This is not to idealize colonialism, but rather to highlight that people—especially those like the Kunama who were often caught between warring factions—sometimes saw colonial powers as a buffer against more immediate threats. If not this, Italian colonialism was seen as a force for exporting civilization. Although not ideal by our modern standards, the road-building mentioned is a classic example of corvée labor—compulsory but compensated work—that many states, even non-colonial ones, have utilized. In this way, even when labor couldnt be compensated through payment, it was compensated through goods the Kunama would've appreciated.

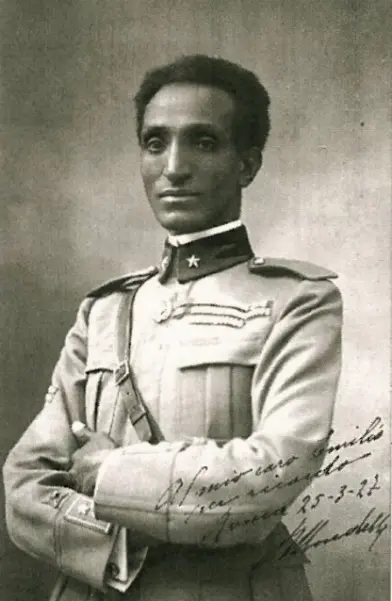

Some reading this might be tempted to think that I am cherry picking from the Kunama, but here are other examples of enthusiastic natives desiring enlistment in colonial institutions. Some Tigrinya lamented not being allowed to join the Italian army:

"...We cannot be enlisted in the Italian army because a person named Hamid prevented us. We curse that Hamid be stubbed."

This tells us that military service under the Italians was not universally loathed—it could be seen as honorable, and even desirable [as men in the warrior classes are typically seen in high regard in many parts of the world, and if for nothing else, women love a man in uniform], especially when local alternatives included famine or tribal conflict. Indeed, the Oromo and Sidama peoples also allied with Italy during its campaigns against the Ethiopian Empire.

It is not unreasonable, then, to ask what might have happened if Italy had remained in a leadership role in East Africa after the fall of Fascism. Unlike indirect rule, where colonial authorities used local chiefs (often exacerbating tribalism), direct rule by a distant European monarch offered a form of impartial governance. An Italian king did not represent the interests of any one local group, and therefore may have fostered unity in a way that local rulers could not.

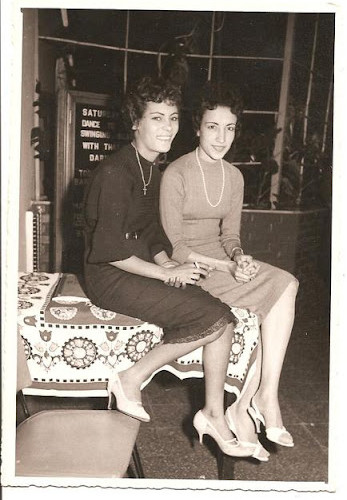

Had Italy maintained control, perhaps Eritrea would have seen a developmental trajectory more like Canada, Australia, or Hong Kong under British rule; places which had completed their colonial maturation cycle when they had gone independent or been released from colonial rule. Of course difficulties would’ve presented itself, as progress seldom is ever a straight line, nor without low points. However, Kunama (and general Eritrean) access to infrastructure, markets, cultural life, and education might have helped streamline progress. I imagine, that since the western world was moving on a trajectory towards liberalization, that certain humanist protections would’ve been granted for the Kunama. Moreover, with the influx of Italians more mixed marriages would’ve happened, perhaps creating a modest mestizo population. All of which would've resulted in flourishing hybridity—Italian libraries, cinemas, mixed architecture, cafes and gelato shops and fusion foods enriching the urban landscape of Asmara.

Of course, history did not go this route. Since Italy’s departure, Eritrea and the broader region have seen prolonged periods of instability, authoritarianism, and conflict. We cannot say what might have been. But we can at least acknowledge the full spectrum of historical memory, including those who saw colonialism as a step—however fraught—toward peace and prosperity.

In doing so, we reject the caricature of the colonized as merely passive victims or noble rebels. The Kunama remind us that historical agency takes many forms, and that sometimes those forms include cooperation, adaptation, and even appreciation. Their voices deserve to be heard alongside the rest.

Perhaps, in remembering them, we can sit down and enjoy a gelato—not as a symbol of imperial nostalgia, but as a quiet testament to the complexities of our shared human past.

Comments